How One State-Based Community Foundation Found Space for Climate

by Michael Kavate

Inside Philanthropy, June 11, 2021

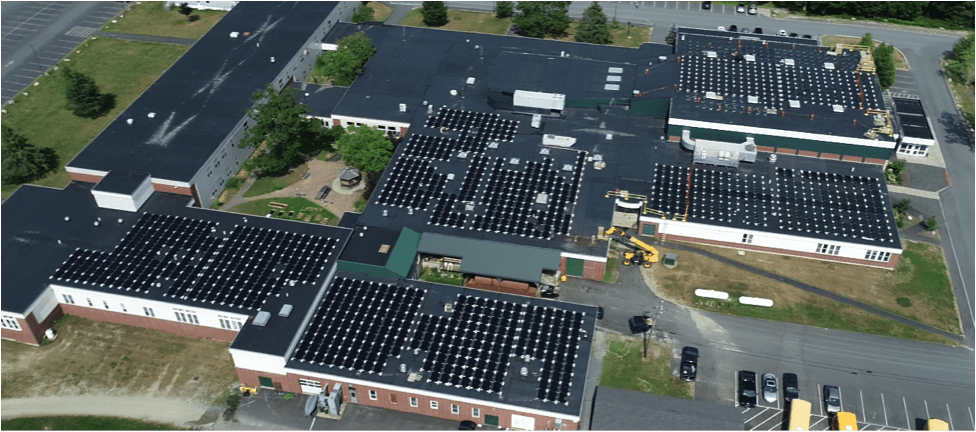

The Mount Desert Island High School was the first school in Maine to produce all of its electricity through rooftop solar panels. A Climate to Thrive, a MaineCF grantee, facilitated the rooftop solar installation by connecting and supporting students, administrators, and contractors. Photo credit: Sundog Solar

Five years ago, after holding meetings in each of the state’s 16 counties and dozens of conversations with community partners, the Maine Community Foundation (MaineCF) settled on five key goals for its new strategic plan. Tackling climate change was not among them.

Yet today, the foundation is on its way to incorporating climate change as a focus across many of its programs. Despite limited staff time and tight resources, the institution has found ways to add climate change considerations to its existing portfolio without creating a stand-alone initiative. A passionate share of its donor base had a lot to do with that, with 67% indicating that the environment was one of their leading priorities in a 2018 foundation survey.

“It’s a lot like the work we’ve done on racial equity,” said Maggie Drummond-Bahl, senior program officer. “We’ve begun to think about racial equity as a lens in all of our grantmaking and understand it as a value that influences everything. We’re on a track of having climate change have a similar role in our work. We’re maybe not quite there yet, but it certainly seems to be playing out that way.”

As projections highlight the need for a massive push to halve world emissions from recent levels by 2030 to prevent the most catastrophic impacts of climate change, MaineCF’s approach offers lessons for any philanthropy looking to take action but unable to launch new bodies of work or funding.

Its actions are also an illustration of the new leeway some institutions are feeling as political currents shift on climate change. Community foundations in deep-red counties like Sarasota, Florida, are accelerating their efforts on climate, while Democratically controlled cities in red states, such as Cleveland, are rolling out a variety of measures. In Maine, the state’s prior governor, Republican Paul LePage, vetoed numerous bipartisan measures on climate, banned new wind energy projects and suggested climate change would benefit the state. But the 2018 election of Democratic Governor Janet Mills has sparked climate action throughout the state.

“That just unleashed the power of the community foundation to engage in this work,” said Alexander “Sandy” Buck Jr., president of the Horizon Foundation, one of the Maine Community Foundation’s frequent partners. “They try to stay apolitical, which I applaud them for, but they do put their money, maybe, where their mouth isn’t.”

Three ways MaineCF integrated climate

Energy efficiency is one of three primary prongs of MaineCF’s climate work. Between 2014 and 2017, the foundation received roughly $1 million through a Community Foundation of Atlanta pilot program to help Maine nonprofits make weatherization and energy efficiency improvements to their buildings.

It was a learning experience. The program was complicated and took a lot of staff time, so when it ended, the foundation looked at how it could continue in a revised form. MaineCF ended up adding an energy efficiency component to an existing initiative, the Belvedere Historic Preservation Program.

With support from that program, nonprofits have made energy efficiency upgrades and replaced outdated equipment, like oil-fired boilers and furnaces, typically leading to big savings on energy bills. For instance, in 2019, MaineCF support paid for an energy audit at the Carver Memorial Library in Searsport. The next year, the program helped the library pay for a new heating system, attic insulation and energy-efficient lighting. Through 2020, the program has awarded more than $300,000.

MaineCF has taken a similar approach as it incorporates climate change into its conservation work, which makes up the second prong of its climate strategy. In 2018, the foundation received a surprise bequest that led to an overhaul of its existing conservation grant program. The two programs that emerged—Conservation for All, which focuses on increasing access for underserved populations, and Maine Land Protection. Both prioritize projects with a climate component.

Only one grant cycle has elapsed since, with no climate-focused projects. But the team is hopeful about what’s to come. Drummond-Bahl said MaineCF would love to see a proposal that focuses on the protection of the state’s salt marshes, which are key to mitigating climate change and promoting resilience. Sea level rise may be a topic for many other potential projects.

“It remains to be seen what some of those transformational projects might be,” she said. “We’re at the beginning of our learning process on this.”

The third prong of the community foundation’s climate work has been to host the Maine Climate Leadership Fund, which supports the Maine Climate Council, a group of business, nonprofit and government representatives assembled by the new governor.

Private foundations and donors who want to support the council but cannot or do not want to write checks to the state can contribute to the fund instead. The fund has awarded $185,000 to the state of Maine to date, with 11 donors contributing this year. “That was a way we could use the unique role of a community foundation to support that work,” Drummond-Bahl said.

Buck of the Horizon Foundation, the lone philanthropic representative on the council, said MaineCF’s seal of approval was a big help as philanthropic interest in the council grew.

“The community foundation was terrific,” said Buck, whose institution also supports the community foundation’s energy efficiency program. “It’s very helpful when it comes to reaching out to donor advisors that we don’t know about, that maybe want to keep a lower profile but are interested in contributing to a larger cause.”

Leveraging its connective power

Beyond its own programs and operations, MaineCF has found ways to leverage its connective role as a community foundation.

For instance, the foundation recently got a proposal for a feasibility study on electrifying the entire Maine lobster fleet by 2050. The team tracked down two donors to fully fund the $20,000 project. In a similar way, they brought together donors to cover a portion of the $30,000 budget of a summit by the Maine Environmental Education Association on developing a climate science curriculum.

“Some of those kinds of projects come across our desks, and because our donors care so much about those issues, we’ve been able to support that work by using that match-making function that we have,” Drummond-Bahl said.

MaineCF has also helped connect the local philanthropic community around climate issues. Along with the Maine Philanthropy Center, the community foundation started the Environmental Funders Network, which brings together an informal cohort of roughly 100 green funders in the state, and now boasts a two-dozen-member Climate Funders Group. This was a marked change for the state’s green funders.

“There wasn’t any kind of a network” on environmental issues prior to that, Buck said. “There’s nothing worse than, kind of, operating in a silo, not really sure what’s going on, throwing grant dollars at things and not knowing what to expect.”

Many community foundations have avoided the phrase “climate change” even as they mount efforts to confront it. Tahoe Truckee Community Foundation, for instance, focuses on forest health. Gulf Coast Community Foundation frames its approach on individual projects. In part, these choices aim to avoid abstract and politically contentious terms, i.e., “climate change,” and stay centered on what’s of local importance. That’s a natural and often winning instinct for community foundations.

MaineCF, by contrast, has always used the phrase “climate change” to describe its work on that front, partly due to strong support from donors. Yet it’s only over the past year that MaineCF has brought all those different elements together in sharing its work with donors and the public. And according to Drummond-Bahl, there are many more steps the foundation wants to take.

“There’s certainly more that we can do and I think we will do,” she said. “We try, within the funding community particularly, to find the unique roles we can play.”

--This article appeared in Inside Philanthropy, June 11, 2021. Posted with permission.